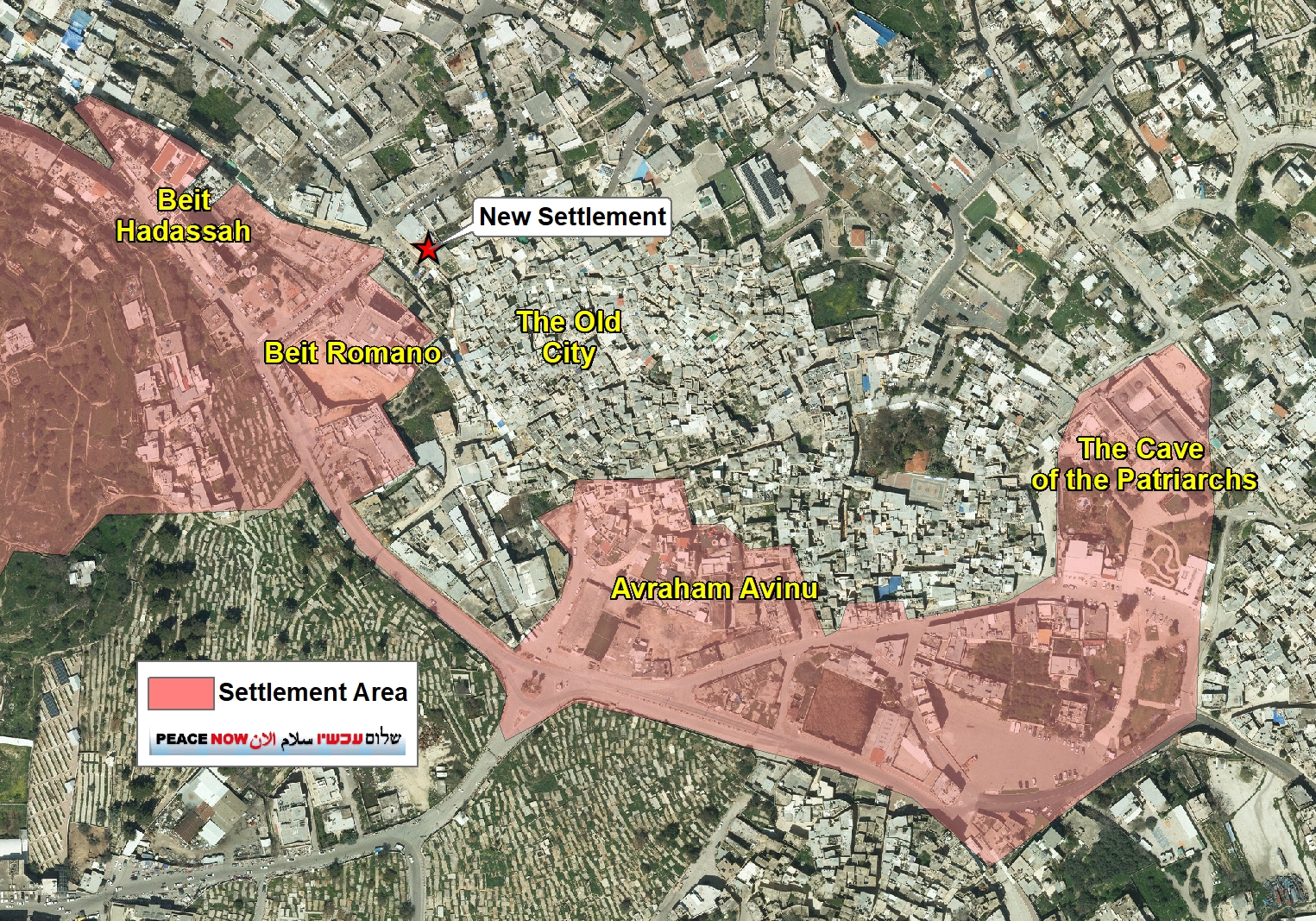

On Tuesday (2/9/25), settlers from the Shavei Hebron Yeshiva entered a building on Shallala Street in Hebron and established a new settlement there. Shallala Street, where the settlement was established, has in recent years become the main route for Palestinians to access Hebron’s Old City and the Ibrahimi Mosque, after the parallel street, Shuhada Street, was closed by the Israeli army to Palestinians. With the establishment of the new settlement, there is concern that the army will also close Shallala Street to Palestinians under the pretext of protecting the settlement, which would almost entirely block Palestinian access to the Old City of Hebron from the west.

Peace Now: “This settlement is a direct initiative of the government. The Custodian of Government Property allocated the building to the settlers, and the army opened a special passage for them to enter. The goal of establishing a settlement in the heart of Hebron’s casbah is to seize new areas of the city and displace Palestinians from them, similar to what was done in the city center around the existing settlements. The settlement in Hebron is the ugliest face of Israeli control in the territories. Nowhere else in the West Bank is apartheid so blatant. Establishing a new settlement in Hebron is a provocation that harms Israel’s political and security interests.”

The new settlement in Hebron (“Beit Valero”) – beyond the fence separating the settlements from Shallala Street, Hebron, 3/9/2025

Allocation of the House to Settlers by the Government – Implementing the “Right of Return”

The house that the settlers entered had belonged to a Jewish family (the Moïse Valero family) before 1948. After the 1948 war, the property was under the management of the Jordanian government, along with other Jewish-owned properties in Jordanian-controlled territory. After 1967, these Jewish properties came under the management of the Custodian of Government Property in the Israeli Civil Administration.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Israeli governments allocated four such Jewish-owned properties in Hebron for the establishment of four settlements in the heart of the city: Avraham Avinu, Beit Romano, Beit Hadassah, and Tel Rumeida. In 2016, the Custodian allocated another plot adjacent to Beit Romano for the construction of 31 settlement units, and later also decided to allocate the wholesale market buildings adjacent to Avraham Avinu settlement for settlers (a plan not yet implemented). Now, for the first time, the Custodian has allocated a property in Hebron outside the existing settlement areas.

About two decades ago, the heirs of Moïse Valero petitioned the Israeli High Court demanding that the property be returned to them, or alternatively, that they receive compensation for its confiscation by the Civil Administration. The court ruled that since 1948, when the property was transferred to Jordanian government control, the private ownership rights of the original owners had effectively been severed, and that the issue of ownership must be resolved in the political sphere.

Justice Procaccia wrote in the ruling: “The transfer of the property to the [Jordanian] Custodian of Enemy Property severs the private ownership link of the original owner to the property and shifts the resolution of its fate to the political and international arena, within the framework of inter-state agreements. We hope and wish that the day is not far when such agreements will indeed be reached.”

Between the lines, one can read the other side of the coin: inside Israel there are hundreds of thousands of properties, buildings, and lands that were owned by Palestinians before 1948. The Israeli government decided that these properties would not be returned to their Palestinian owners, and the Knesset even legislated the Absentees’ Properties Law to that effect. Restituting Jewish property lost in Hebron in 1948 opens the door for Palestinian claims to return Palestinian property to the heirs of refugees, and this was one of the reasons for the court’s ruling. Nevertheless, the Israeli government chose today to allocate the Hebron property to Israelis. The Civil Administration allocated the building to the Shavei Hebron Yeshiva, which announced it would use it as housing for its students.

The New Settlement: Risk of Closing a Vital Street to Palestinians

In recent decades, the reality in Hebron has been that in order to protect a few hundred settlers (about 800) living inside a Palestinian city of some 250,000 residents, the Israeli army has closed roads and streets to Palestinians. In the city center there are streets where Palestinians are forbidden even to walk; hundreds of homes and shops have been shut down by military order or because Palestinians are denied access; and Palestinians entering the area must undergo security checks.

Shuhada Street, once one of the busiest streets in Hebron, became deserted of Palestinians. Immediately after the 1994 massacre perpetrated by Baruch Goldstein against Muslim worshipers at the Ibrahimi Mosque, the army closed the street to Palestinian vehicles, and since 2002 it has been closed also to Palestinian pedestrians. The parallel street, Shallala Street, has since become the main – and almost only – road leading to Hebron’s Old City (the casbah) and the Ibrahimi Mosque.

The new settlement is located outside the existing settlement areas, on Shallala Street, near the entrance to the Hebron casbah. The army’s security approach is that in order to protect settlers, restrictions are imposed on Palestinians. In Hebron, this has meant street closures and security checkpoints. The new settlement could lead the army to impose further restrictions on Shallala Street, and possibly close it entirely to Palestinian movement.