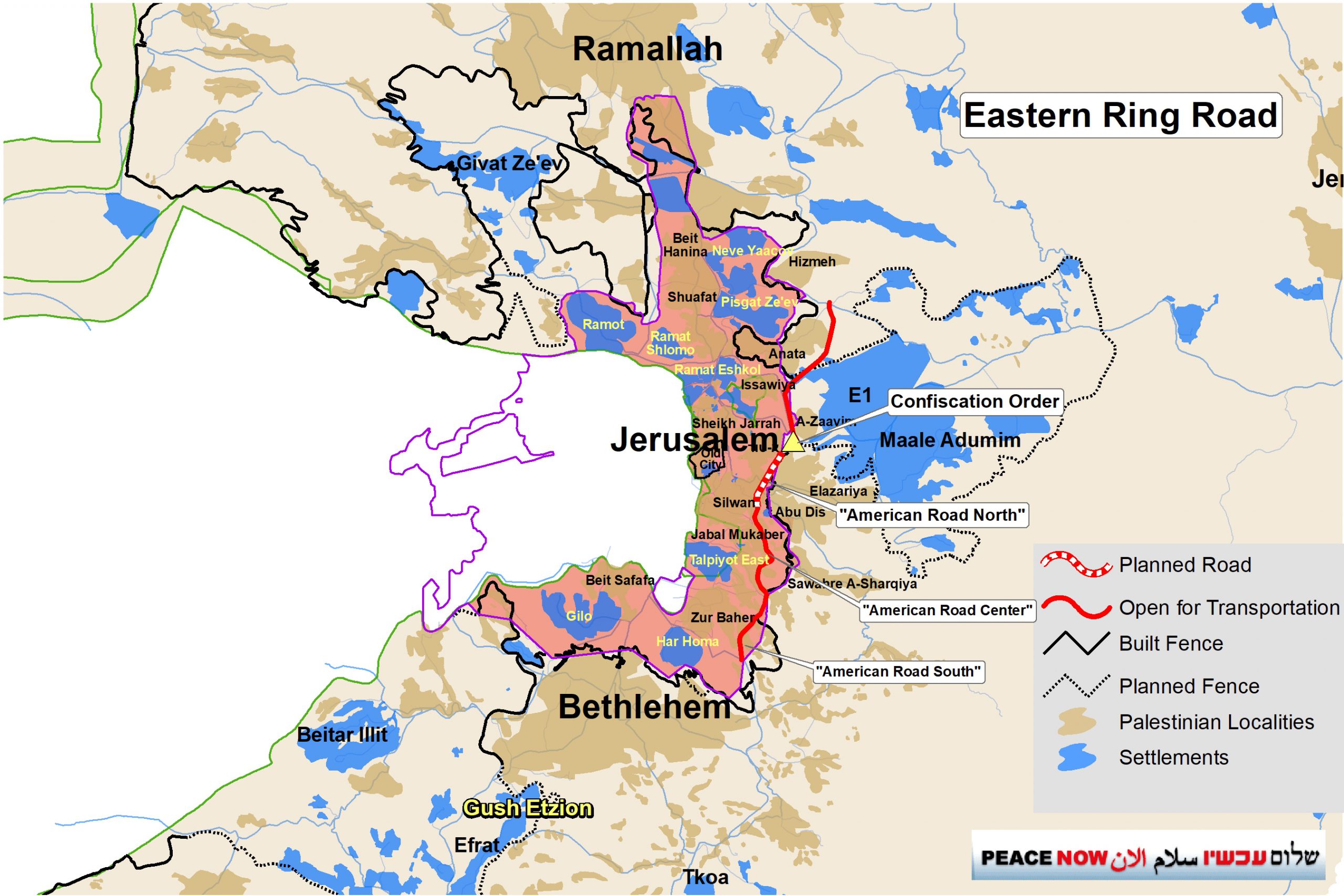

Peace Now has learned that about two weeks ago, an expropriation order was issued for about 55 dunams of A-Tur lands east of Jerusalem for the purpose of paving the northern part of the Eastern Ring Road. The Eastern Ring Road is planned to bypass East Jerusalem from the east, and connect the settlements south of Jerusalem in the Bethlehem area with the settlements east of Jerusalem in the Ma’ale Adumim area and east of Ramallah. So far, the southern part and the central part of the road have been paved, but the northern part, which is estimated to cost close to NIS 1 billion, has not yet begun to be built. The expropriation order is part of the preparations required before the paving of the northern part may begin. In addition, it turns out that in March of this year, an application for a building permit was submitted to the Jerusalem Municipality for the paving of the road on the “Jerusalem side” of the road. The permit issuance process is expected to take at least several months, and is a necessary procedure before works on the ground can begin.

As far as Peace Now knows, the Ministry of Transportation has not approved the transfer of funds for the start of work (over NIS 900 million), but it seems that preparations for the paving are in full swing so that as soon as there is a political opportunity and the budget is approved, the paving can begin immediately.

If the Eastern Ring Road is completed, it will immediately lead to the accelerated development of settlements in areas in the heart of the West Bank. At the same time, the Palestinian population of the West Bank will not be able to use the road because it passes within the area annexed to Jerusalem and within the separation fence, and access to it is only through checkpoints that Palestinians are not allowed to pass.

Peace Now: This is a strategic road designed to bring about accelerated development in the settlements, but the Palestinians, from whom the land is being expropriated, will not have access to it. When Israeli policy in the territories is to develop infrastructure and construction for one population, at the expense of the resources of the other population, it is called apartheid. The government continues to lead us to the reality of one state of discrimination and oppression.

Background: The Eastern Ring Road

The Eastern Ring Road is a huge infrastructure project that has been promoted in recent years. It is planned to be a main artery axis that connects the southern part of the West Bank to the north. There is a critical need for such a longitudinal axis for Palestinian development in the West Bank, but the road paved by Israel is blocked to the Palestinians by the Separation Barrier that Israel erected around East Jerusalem, and it passes through territories Israel annexed in 1967 in East Jerusalem where Palestinian access is forbidden unless with special permits.

It turns out that the road is actually intended to serve only the Israelis, settlers, and to some extent also the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem. All Palestinian transportation in the West Bank between north and south is forced to continue on one long, winding road east of Jerusalem (Wadi Nar), through towns and villages in ever-increasing traffic jams and congestion.

Status of works on the Eastern Ring Road

The eastern ring road is divided into three main parts: the southern part, the central part and the northern part. The government hired the services of Moriah, a construction company owned by the Jerusalem municipality that specializes in large infrastructure projects, to manage and execute the project. In government and municipal documents the road is also referred to as the “American Road” (after a road that began to be built before 1967 under the Jordanian authority by an American company in the Jabal Mukaber area where part of the planned ring road passes).

The southern part (“American Road South”) – a road from the Umm Tuba and Har Homa area in the south, in the direction of Zur Baher and Jabal Mukaber, about 2.4 km long. The road connects to the “Lieberman Road”, a bypass road to Bethlehem that Israel has paved for the settlers in the southeastern part of Bethlehem (the settlements Tkoa, Nokdim and more). The southern part of the Eastern Ring Road was opened to traffic about a year ago and was built at a cost of about NIS 150 million from the funds of the five-year plan for the development of Palestinian East Jerusalem allocated by the Israeli government (Resolution 3790), see below.

The central part (“American Road Center”) – this is a 3.3 km long road that crosses the Jabal Mukaber neighborhood, along an old and narrow road. The old road has undergone significant widening and upgrading and has recently been opened to traffic. The municipality is promoting a very problematic construction plan along this road that allows almost no additional residential construction.

For the central part, an alternative is planned of a highway that bypasses Jabal Mukaber from the east. These days, the Moriah company is spending millions of Shekels into the preparation of the detailed planning of the alternative (which in the plan documents is for some reason referred to as the “Zur Baher Bypass”) about 3.4 km long of a highway with bridges, tunnels and interchanges. The construction of this part of the road involves the movement of the separation fence and it is probably one of the reasons why in the meantime the alternative of upgrading the municipal road within Jabal Mukaber has been paved.

To date, approximately NIS 165 million has been invested in the central part (both the paving of the municipal road and the planning of the alternative highway) of the five-year plan for the development of East Jerusalem (Resolution 3790).

The northern part (“American Road North”) including the “Sheikh Inbar Tunnel” – the northern part of the Eastern Ring Road is the most pretentious part about 3 km long, of which 1.6 km in a tunnel under Palestinian neighborhoods, as well as two bridges. The cost of this section is estimated at over NIS 900 million. Last year, the detailed planning of the road was completed, at a cost of tens of millions of NIS. The next stage is the execution stage, and it depends on the transfer of the budget required by the government.

In March 2022, the detailed planning documents were submitted to the Jerusalem Municipality for the purpose of opening a file for a building permit, a procedure that is required before the bulldozers can start the works, and is expected to take several months. On May 2022, the expropriation order for the lands outside the municipal borders was issued. The various government agencies are completing the bureaucratic preparations so that once there is a political opportunity and the funds are approved, the works can start immediately.

The construction of a bridge at the Southern part of the Eastern Ring Road, East Jerusalem, May 2020

“Expropriation for public purposes” (Israeli public only)

When there is a public need for land, the law allows the state to expropriate private land, and the landowners are entitled to monetary compensation from the state. In the case of the Occupied Territories, international law as well as Israeli case law stipulate that Israel must not expropriate Palestinian land for use by Israelis unless the Palestinian residents can also benefit from it. It was therefore not possible to establish settlements by way of expropriation for public purposes (but the legal system was able to find legal tricks that allow other ways of taking over land), and the expropriations made in the West Bank are usually for roads and infrastructure for the benefit of the general public.

In the confiscation order issued two weeks ago by the head of the Civil Administration the purpose of the confiscation is described as follows:

“By virtue of my authority … and after I was convinced that the acquisition of ownership of the land is in the public interest for the purpose of constructing a road known as “the American Road North” in a manner that provides a response to public, transportation and safety needs … I hereby decide to acquire ownership of the land described below”.

In the case of expropriation for the purpose of the Eastern Ring Road, Palestinian residents will not be able to enjoy it because, as stated, the road passes through the territories annexed to Israel and Israeli governments prohibit Palestinians from entering its territory except with special permits. In fact, the part of the road in the expropriated area is on the “Israeli side” of the Separation Barrier, and Palestinians have no access to it.

That being the case, the “public interest” in whose name the head of the Civil Administration expropriates the land is only the interest of the Israeli public, and not the Palestinian public. Unfortunately, past experience shows that expropriations of land for the purpose of roads leading into Israel and in fact closed to Palestinians, have been approved by the legal advisers and even by the courts. This was the case with the train route from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv, which passes partly through the West Bank; and this was the case with the Ben Zion Interchange, which connects Beit Hanina with Road 50, and in other cases.

In this context, it is worth mentioning the words of Supreme Court Justice Aharon Barak in the judgment of Jam’iat al-Iscan, which dealt with the expropriation of land in the Occupied Territories (HCJ 393/82 – Jam’iat Iscan Al-Ma’almoun v. Commander of the IDF Forces):

We have seen that the considerations of the military commander are ensuring his security interests in the Area on one hand and safeguarding the interests of the civilian population in the Area on the other. Both are directed toward the Area. The military commander may not weigh the national, economic and social interests of his own country, insofar as they do not affect his security interest in the Area or the interest of the local population. Military necessities are his military needs and not the needs of national security in the broader sense (HCJ 390/79 [1], at 17). A territory held under belligerent occupation is not an open field for economic or other exploitation. Thus, for example, a military government is not permitted to levy taxes intended for the coffers of the state on behalf of which it operates on the residents of a territory held under belligerent occupation (HCJ 69/81, 493 [5], at 271). Therefore, the military government may not plan and implement a road system in an Area held under belligerent occupation if the purpose of this planning and implementation are simply to constitute a “service road” for its own state.

Funding for the road – from funds allocated to the development of Palestinian East Jerusalem

Resolution 3790 – On 13/5/18, the Netanyahu government decided to allocate NIS 2.1 billion over five years to “reduce socio-economic disparities and economic development in East Jerusalem.” This is the largest government investment in Palestinian East Jerusalem since 1967. The budgets were allocated mainly to the fields of education, transportation, employment and welfare. It turns out that considerable sums of the allocated funds went to the Eastern Ring Road. According to the government report on the status of the decision in 2021, NIS 380 million was invested in the Eastern Ring Road.

However, as mentioned, the main purpose of the road is to serve the settlers, even if parts of it can certainly serve the Palestinian residents of Jerusalem and facilitate the passage between the Palestinian neighborhoods in the southern part of the East Jerusalem. The fact that this is a road intended for the development of the settlements was explicitly written in the government status report:

“The American Road is intended to be an alternative to the congested Derech Hebron Road, to connect the neighborhoods of East Jerusalem and allow quick access for residents of Gush Etzion and Maale Adumim to and from Jerusalem.”

And in one of the planning documents of the northern part it is written in greater detail about the real purpose of the road and the settlements it is intended to serve:

“Its purpose is to allow access from/to the southwest of the city (Talpiot and Malcha), from/to Jordan Valley settlements, Maale Adumim, Geva Binyamin and the northern neighborhoods of Jerusalem”.